Windows into Our Lives

Maddie Bender

Two years ago, my monolingual family and I watched a Passover seder in Spanish over the video-conferencing platform, Zoom. The Passover Zoom was unlike any other, in no small part because it was conducted in a foreign language. I don’t remember the reasoning behind this decision, but I recall crowding around an iPad positioned at one side of our dining room table, which we took turns using as a classroom and meeting space during the day. It goes without saying that during April 2020, we were conducting our lives almost exclusively from the confines of our apartment, and the platform that enabled our virtual existence was Zoom. My mother attended speaker events; my sister went to high school; and I played online Yahtzee with a group of friends well into the witching hours.

The era of distanced life that began for many of us in 2020 can rightly be called a diaspora for Jewish communities. Yet, unlike any previous ones, the perpetrators of this virtual diaspora were not human, but rather viral. I can’t say for certain that my Passover experience was unusual; in fact, certain aspects of it—the general sense of confusion, the number of times we were reminded that what we were experiencing was “unprecedented”—felt close to universal.

Looking through the Collecting These Times archive, one finds a multilayered, shifting relationship between Jews and Zoom. Earlier submissions shine light on the process of adopting a new system for religion, education, and community, and the growing pains associated with the switch. We see religious leaders grapple with what is acceptable in an emergency, and where “unprecedented circumstances” fade into a new normal. Just as quickly, tensions arise between competing priorities of inclusivity and protection.

And then, a Zoom Boom: the platform’s use expands to b’nai mitzvah, mourning, religious observance, and education. In parallel and in ways that intersect, the archive reveals the writing and re-writing of best practices. Zoom wears many hats, and serves as many functions as a high school multipurpose room.

Yet, at what could be considered the height of Zoom, submissions coalesce around a widely shared sense of aimlessness, and a desire for identity that is at odds with the nature of this platform. In evolutionary biology, living organisms are often categorized as either “specialists” or “generalists.” While generalists are often more abundant worldwide, they tend to fare poorly in highly idiosyncratic environments. In other words, generalists are generic. Zoom is like that, and Jews have been struggling to personalize the impersonal, to rediscover community, and redefine its bounds.

“I wondered whether this is what God experiences”

Jewish communities did not all happen to arrive at Zoom coincidentally, or because of savvy marketing from wall advertisements in JFK airport. Instead, congregations chose a platform that most closely resembled the dynamics of in-person services, events, and education. A document from The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly composed to guide the Conservative movement summed up the history of virtual observance in order to rule on the acceptability of streaming services during Shabbat and the high holidays.

Prior to the pandemic, they wrote, congregations that streamed services were using one-way platforms, like YouTube and Facebook Live. But when in-person congregating became unsafe, communities opted for more interactive platforms. This isn’t as heady as it sounds—foundational prayers like the Shema and Kaddish are call-and-response, participatory at their core. Praying together means being able to hear others and be heard.

The document grapples with whether streamed services violate the rules or spirit of Shabbat, noting that their ultimate ruling to permit the activity sets a precedent, as “[t]here will also be significant pressure to continue some type of streaming option even after the current crisis” for those who cannot attend services in person.

Of course, permitting services to be streamed or “Zoomed into” brought up entirely new lines of questioning. Certain submissions draw attention to the altered definition of a minyan, or quorum needed for some prayers and religious obligations. “Could you technically be part of two minyanim at once?” prompted an email chain among Conservative rabbis. The rabbi posing the quandary noted he is doing so “more as a philosophical question,” since the consensus is a cut-and-dry “no.” However, the explanations put forward vary; a notable reply to the email chain reads, “Only God can be in multiple places at the same time, because the Divine is not material and thus does not occupy any space. However, I recently simultaneously attended by [Z]oom a funeral in Philadelphia and one in Toronto. I wondered whether this is what God experiences.”

While on lockdown in Israel, one Jewish Theological Seminary student took a lighthearted approach to solve the problem of making a minyan. Though she attended services over Zoom, she felt “a sense of isolation” and distance from the people on the screen versus the objects in her home—particularly Grey Bear, her teddy bear. “More than Zoom minyanim, my own stuffed animals and artifacts in my apartment felt present to me,” she wrote. These early pandemic experiences share a desire to make sense of something new and strange by putting it into a known context; even still, it is clear the fit is not perfect but instead approximate. Over time, these irregular edges will start to chafe against our aspirations for a virtual community.

“More than Zoom minyanim, my own stuffed animals and artifacts in my apartment felt present to me,” she wrote. These early pandemic experiences share a desire to make sense of something new and strange by putting it into a known context; even still, it is clear the fit is not perfect but instead approximate. Over time, these irregular edges will start to chafe against our aspirations for a virtual community.

“Some sad version of The Brady Bunch on a monitor”

Unlike other streaming platforms—public accounts on YouTube or Facebook Live, for instance—Zoom’s access can be restricted by enabling password-protected spaces. The encryption was reminiscent of the security measures (guards, metal detectors) that were commonplace at the synagogues I attended growing up: a sad but necessary protection. What may have seemed like a minor consideration in this virtual space would unfortunately become relevant early on.

In April 2020, the Anti-Defamation League (ADF) compiled a list of antisemitic “Zoombombing” incidents—where uninvited users crash a meeting and disrupt it, often by saying hateful comments aloud or writing them in a public chat. Nearly as quickly as events switched to being hosted on Zoom, there were enough of these antisemitic incidents to compile an entire list. As the ADF stressed, the perpetrators weren’t always “bored” teens undertaking pranks, unlike many reports at the time that downplayed them as such. Indeed, some were affiliated with extremist groups.

Of course, so much of the appeal of Zoom as a platform is that it could enable much more than services, which could have been as easily streamed on another platform (though, arguably, less successfully.) Community meetings, life milestones, and education would all come to play important roles in the Zoom menagerie.

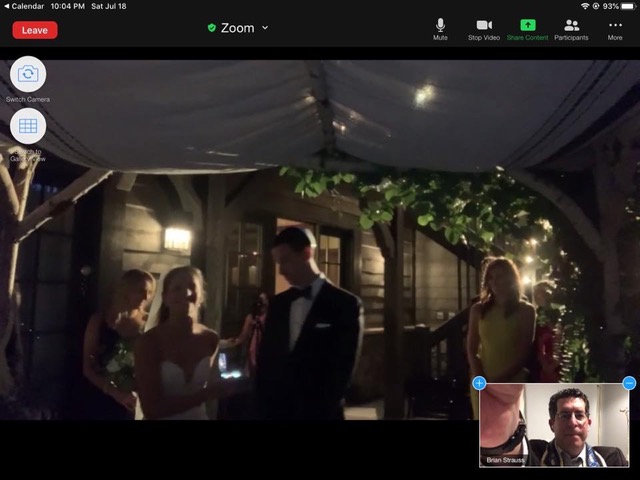

Some experimented with adapting the event to the new format, a lighthearted example being when one family had “Elijah” show up as a participant in their Zoom seder. One Houston, Texas couple, held a hybrid wedding, in which a rabbi Zoomed in to officiate. But there were also countless Zoom calls that were not so joyous. The United States not long ago surpassed one million deaths from this virus—always inescapable, death seemed to loom even larger on Zoom. The traditions of mourning, particularly sitting shiva, were transferred to Zoom formats. But as one writer reflected while sitting shiva for her father-in-law, a Zoom shiva was better than isolation, but at times only marginally so.

“Like some sad version of The Brady Bunch on a monitor, people from all points in my husband’s life dropped in and out to pay their respects,” she wrote.

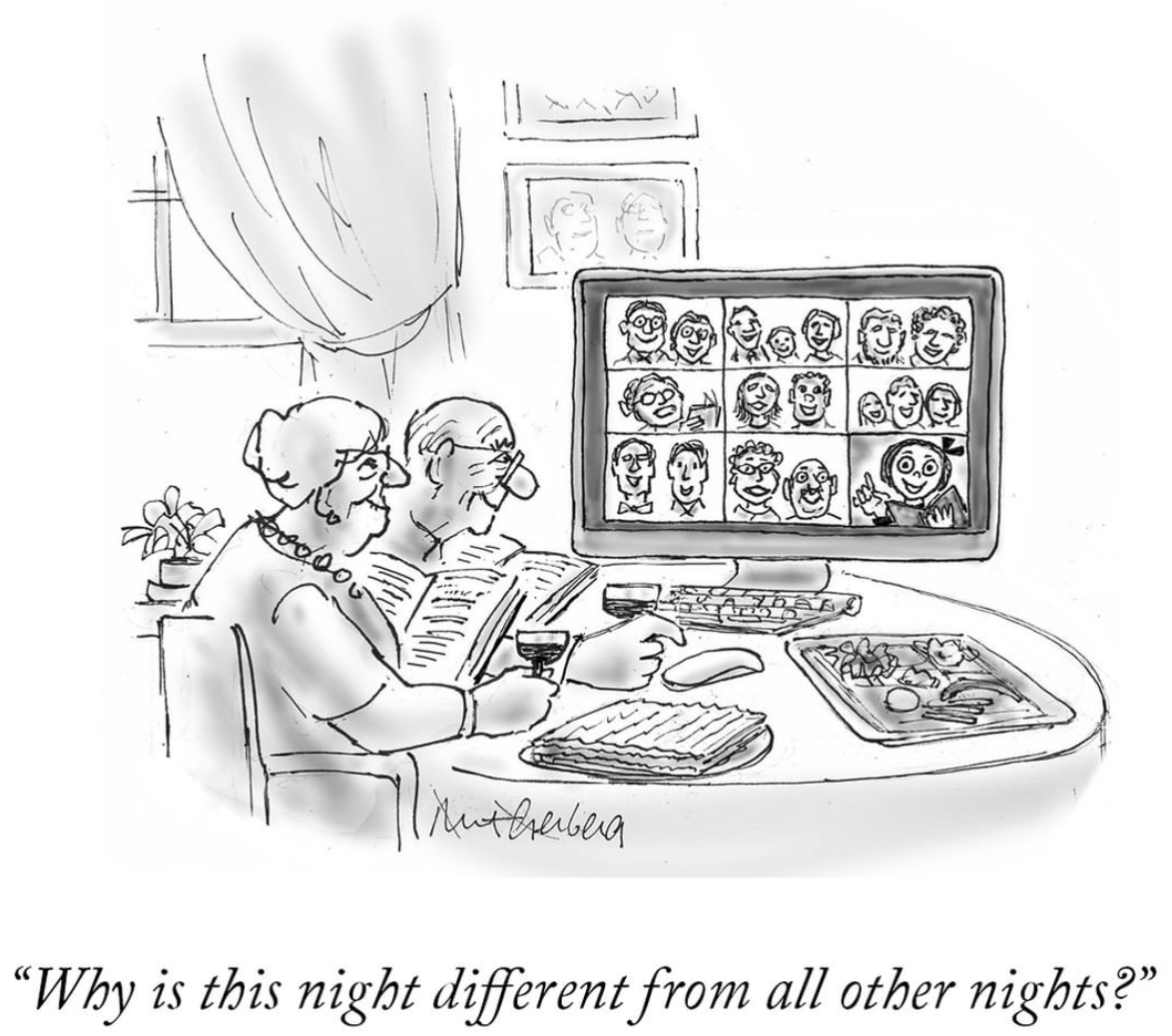

An online New Yorker cartoon from April 2020 satirized the same format in the context of the Passover seder. We see doting grandparents look on with a smile as a young child recites the Four Questions in one of the nine windows on their screen. The caption, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” plays at the content of these questions; the sheer absurdity of asking what could be different that year than from past seders; and, lastly, the bittersweet reality that for many families on lockdown, Zoom meetings with relatives became a regular occurrence. If the family shown attending this Zoom seder was anything like mine, not much set that night apart from others, but for kosher wine and slightly more singing.

The decision to highlight digitally capable older individuals in the foreground of the cartoon, looking on with soft smiles, was an optimistic one. For the most part, younger people did not need coaching when it came to adapting to Zoom, but accessibility remained an issue for those who were not digital natives. One woman reflected on a moment years ago, when her adult children advised her to buy a computer: “What would I do with it?” she asked at the time. The technology is a constant “puzzle” and “frustration,” she wrote, but engagement is a must. “Zoom and Live Streaming have become the king and queen of the internet.” At the same time, the payoff is incomparable—seeing and talking to relatives in a time of isolation is worth the burden of learning how to decipher the platform.

“Now you can see what everything was like in the past”

Older adults were not the sole group whose access to platforms like Zoom were strained or limited. An End-of-Year report from the nonprofit Jewish Queer Youth (JQY) highlighted a used phone drive for at-risk youth, including those in the Orthodox and Chassidic communities. According to the report, some of these JQY members were not allowed smartphones but instead permitted Kosher phones with internet filters that block social media platforms and video-conferencing.

“In other times, these youth have found computers in libraries or have found their way to our in-person programming. Today, they are left without any access to the support resources they so desperately need,” the report reads.

Because of the nature of their organization, JQY translated their in-person, confidential programming into a complex hierarchy of Zoom rooms. Participants aged 13 to 23 entered a “Welcome Room,” followed by a one-on-one breakout room with a social worker for intake and triage. Then, they would be sent to the main drop-in room, and depending on the programming (a movie screening, a discussion series, etc.), they may then be directed to additional breakout rooms for smaller conversations.

The report noted a phenomenon they had discovered in 2020: “As reported by many organizations serving teens, there is a new phenomenon called ‘Zoom Fatigue’. This is exemplified by a growing frustration (and sometimes even animosity) to Zoom programming over time.”

Zoom fatigue impacted myriad Jewish spaces, from social ones set up by organizations like JQY, to educational ones. Middle school students from Politz Day School in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, submitted reflections in 2021 on how the pandemic affected their learning. Eliana, a 7th-grader, wrote, “Being on Zoom made me exhausted and by the end of the day, I felt unusually drained… I couldn’t do anything fun outside of school because of Covid. Nothing was going right and I was convinced that this year was going to be the absolute worst.” Another student, Noahm, said that he and his classmates were enjoying the later wake-up that Zoom classes afford until May, "when it was getting repetitive and some kids' grades were dropping it was hard to focus."

Some students note that between the 2020 and 2021 school years, Politz Day invested in The Owl, an $999 360-degree speaker, camera, and microphone that lets a remote viewer see and hear an entire room. By then, students were given in-person and remote options, though outbreaks forced students to switch to entirely remote classes for weeks at a time. The Owl was “a big help,” wrote Rochel, though Zoom remained a difficult platform for tests and a distracting one, as classmates were prone to bringing in siblings on camera. With The Owl, “School was harder than the previous years but I liked it better than [Z]oom,” said Ariel.

“To whoever is reading this,” wrote Chava, “I hope COVID-19 is not going around anymore. And since this will be read in the future, now you can see what everything was like in the past.”

“It’s like being held at arm’s length when you want to be embraced”

What is to be made of this multi-year, collective experience? Though we have recently been told this pandemic is officially over, adjusting to new variants and undulating case numbers is an unimaginable “new normal.” Reflecting on how one facet of the pandemic has shaped Jewish identity over the past two years takes as much perspective.

In December 2020, New Voices Magazine published a series of vignettes from their staff about the spaces from which they Zoom. These interiors have taken on new meaning, they write: “In a world where most rooms are virtual, the physical spaces pictured in front of the webcam are the closest many will come to indoor intimacy for a long time.”

Back in May 2020, Roseanne Benjamin, a freelance writer, also reflected on her community and intimacy, explaining why she was struggling without in-person services. Watching one on livestream cannot compensate for the highly collaborative spirit of singing together and being heard. If a woman sings “Ki leolam chasdo'' with her camera and microphone turned off, does anyone hear it? Benjamin feared not.

“They’re trying hard, but it’s like being held at arm’s length when you want to be embraced–you can’t replicate the kinesthetic or sensory experience of being in a place when you’re muted on Zoom,” she wrote. “Is Shabbat even Shabbat without community?”

Two years after that ill-fated Spanish seder, we readied to gather at my grandmother’s house, as a full minyan for the first time in three years. Or at least we were supposed to until I tested positive for COVID-19, placing the first night of Pesach squarely within my seven-day quarantine. My grandmother cried when I broke the news to her. I remembered that two years ago we said, “This year on Zoom. Next year in person!” instead of, “Next year in Jerusalem!” I fantasized that this time we’d say “Last year on Zoom. This year in person. Next year together,” but the virus had other plans for the conclusion of this essay. This year, we are on Zoom again. Next year, may we all be together.

Return to Main Page